One of the most dreaded forms of examination in medical school was viva (short for viva voce which means oral interviews). Here, in a face-to-face interview with your examiners you are asked questions from within (and even outside) the curriculum and are expected to provide answers on the spot. One therefore understands how difficult it is to prepare for these exams and the trepidation that comes with it. To make matters worse, in some courses a poor performance in the viva exam earns you an outright failure in that course, no matter your scores in the written and clinical parts. We called it ‘veto failure’.

In my Biochemistry viva exam during my second MBBS professional exams, I was asked to draw the structure of a cholesterol molecule! I found it preposterous given the exam setting. Already, many of us found biochemistry quite abstract and barely managed to pull through in written exams. To be asked to reproduce this in a viva exam was stretching the limits. Of course I couldn’t draw it off hand (there and then) and I told the examiner so.

I remembered this incident recently while at a conference late last year. During one of the lectures, the speaker cited a quote from the English writer Samuel Johnson, that ‘Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it.’ This was to support a point he made that doctors must carry a smart phone (with internet access) at all times so they can easily access medical information as and when required. He argued that one does not need to know everything. I agree.

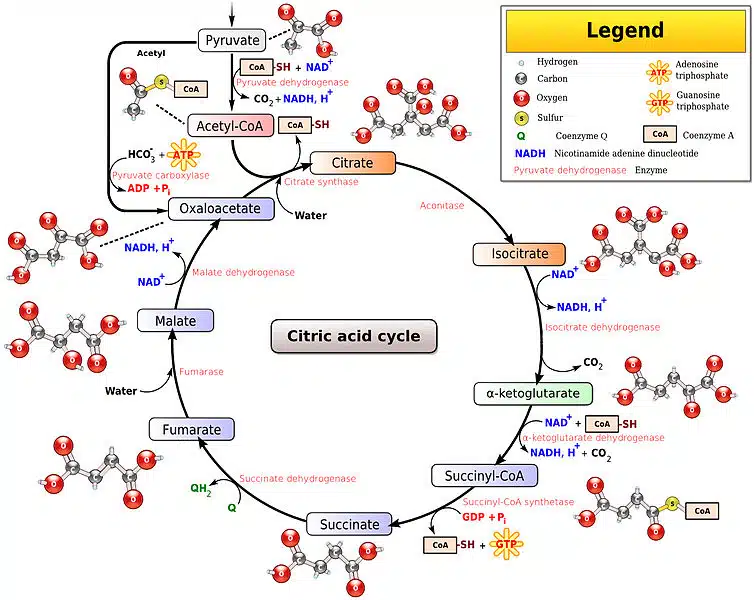

Looking back to the undergraduate and even secondary/high school days, one might wonder if all the things we were taught and made to learn (and reproduce in exams) were really necessary. The image below is called the Kreb’s cycle and has to do with how the body converts food to energy. Medical students are made to learn/cram the entire cycle with all its enzymes and reactions and to reproduce this in exams. In reality, the detailed knowledge of this is not really relevant in clinical practice. This holds true for most STEM courses (I stand to be corrected).

I have come to the realization that the approach to knowledge is cultural. Years back when I was practicing in Nigeria, it was seen as a professional sacrilege to look up information in the medical literature when assessing a patient, including checking the doses of medications! One was seen as a bad doctor if you did that. You were expected to tie all the symptoms into a diagnosis on the spot, and prescribe the correct medications at the correct dosages, even when the cases were complex.

The approach is completely different in the West. Not only are doctors encouraged to look up information while seeing patients, the hospitals are equipped with the relevant infrastructure to facilitate this. In my workplace, UpToDate, the World’s largest online medical resource, is installed in all the computers so that doctors can easily refer to it when seeing patients. Unless absolutely sure, you rarely prescribe a medication without consulting the British National Formulary (BNF).

Once in Nigeria, a friend approached me to berate a doctor who attended to her in clinic. His offence? She peeped at his computer and found he was googling her symptoms. In my experience, there is absolutely nothing wrong with that if done professionally. In fact, we politely ask the patient to excuse us while we check up what they have told us. The art of teasing what is relevant and what is not, and how to apply what was found on the internet in real life is a function of expertise, especially in today’s world of information overload.

It is better to be a safe doctor than a ‘knowledgeable’ one that is unsafe. I would rather have an Engineer who refers to his literature while constructing my house than one who pours what he crammed. One error in his calculations and the house comes tumbling down.

For me, the power of knowledge lies in its application and not just the act of knowing. ‘La cram la pour’ isn’t knowledge. If a lay man and a doctor look up the same symptoms on the internet, the knowledge garnered (and how to use it) will be different. That is what matters. Indeed, knowing where (and how) to readily access information on a subject, and immediately grasping and knowing how to use this information, is as good as knowing that subject.

This is so true. Do you think this procedure can also be adopted by a teacher who may look up concepts and information online before they can go ahead to educate their students…also for other career areas,e.g engineers as you mentioned earlier and others…or is this knowledge procedure only appropriate in the field of medicine. ?

My bro, you’re sound. Well articulated and delivered. Succinctly delivered without living any detail.

Good read

My dad did an MRI scan last weekend. The report was sent to my phone and I read. I’m not a full student, and I’m above average. Everything in that report was written in simple plain English, I even had to google some lines, yet I barely understood what was there not the implications. I understood all was not well sha 😊

It’s the applicability of knowledge that is expertise.

I agree.

I couldn’t agree more! One of my preceptors in the ICU always said, “know your resources.” You don’t have to know everything, you just need to know where to get the information you need.I remember vividly years ago while in anesthesia school, I was transporting a pediatric patient after open heart surgery and my preceptor asked me the mechanism of action and side effects of succinylcholine. Despite my best effort, he wasn’t satisfied. Was that question really relevant at that time? Meanwhile, he kept yelling that I should make sure I don’t extubate the patient in the hallway. Totally unnecessary! Yes, my classmate was asked to “recite” the Kreb’s cycle in the middle of intubation. Good for him, one of those “brainacs,” he recited it. I ask my students questions based on the clinical situation at hand. I don’t do abstracts.

Thanks for this piece