I first met Caroline Elton at a medical conference late last year. Her biography as she was introduced as the next speaker was resounding; an occupational and counselling psychologist specializing in career counselling, with decades of experience behind her. No sooner had she taken to the podium and announced the title of her talk as the same as her book, Also Human, had I gone on Amazon to purchase it (https://amzn.eu/d/fQiNLQ2). It made for an interesting read.

Using real life experiences from her rich practice, she examined ‘the inner lives of doctors‘ arguing, rather pleading, that doctors are also human (like everyone else) and that behind the apparent stoicism lies a heart of jelly capable of feeling emotions. Doctors also cry, get anxious, get depressed, catch feelings, and have sexual urges. Doctors are not anhedonic.

The title of the book is striking. The phrase ‘the inner lives of doctors’ implies that doctors have another life, perhaps‘an outer life’. This apparent dualism stems from society’s erroneous perception of doctors as extraterrestrial beings completely insulated from their patients and incapable of feeling or expressing any emotions. This is wrong. I was in a ward round recently where I struggled really hard to hold back tears that welled up in my eyes as the medical consultant broke the news to an ailing woman’s devastated family that she was dying. Doctors are emotional beings who also cry. They sometimes lock themselves in hospital washrooms to do this! Away from the sight of the public, lest they appear too emotional or too weak for the job. ‘Doctors’ hearts are not made of stone’, she writes.

In Also Human, Dr. Elton argues that doctors face two main challenges: undue expectations from society and inadequate preparation from their trainers. She uses many themes and examples to buttress these points. For instance, on the topic of choosing to study medicine, she reports cases of some of her patients who were coerced into this by their families, only to qualify and realize that medicine was not the right profession for them. The commonest reasons for this were to meet family expectations or to continue family traditions of breeding only doctors.

I had a few colleagues in medical school who had the ill fortune of being in this boat. From a mile away you could tell they were not interested in medicine. One father had to physically attend the campus to upbraid his wards for their poor performance. A year later one of them dropped out of medical school.

On realizing that they are in the wrong career, some doctors try to switch to other professions but find it extremely difficult to do so. Some have gone into depression because of this. She covers this topic extensively in her book. The challenge is that you look back at the grueling years and the arduous effort put into studying medicine and you just can’t let go. Medicine is not something you just drop by the side.

She also touches on how unprepared newly qualified doctors (foundation year doctors or house officers) are for the real world and contends that medical students are not prepped well enough, especially psychologically, for the transition to being ‘actual’ doctors. She gives examples of students who were very bright in medical school but struggled to work as doctors, some eventually quitting. The leap from being a medical student today to being a doctor (with all the attendant responsibilities) the next day could be overwhelming for some and the author argues that there is inadequate support for medical students to successfully make this transition.

She gave an example of a fresh doctor who was left all by herself on a surgical ward on her first night shift with no senior easily reachable (they were in the middle of a surgery in the operating theater). She had to resort to her friend’s mum remotely who had a medical background for advice on how to treat her unwell patients in the ward! This is completely relatable. A few weeks ago I was covering the medical wards overnight when I answered a bleep from a surgical house officer who asked for my advice on how to manage a surgical patient in a surgical ward with a surgical problem! I thought she was mistaken but with a very soft but desperate voice she pleaded that she was alone in the ward and could not reach her seniors and needed help with that patient urgently. Her seniors were busy in the theater!

How about the emotional and sexual needs of doctors? How do doctors cope with breaking the bad news of an incurable cancer to a 40-year old woman, or the loss of a precious baby to a desperate couple, or that an only child had just been declared brain dead in the Intensive Care Unit, and still go home to their families after work, smiling? This is covered in the book.

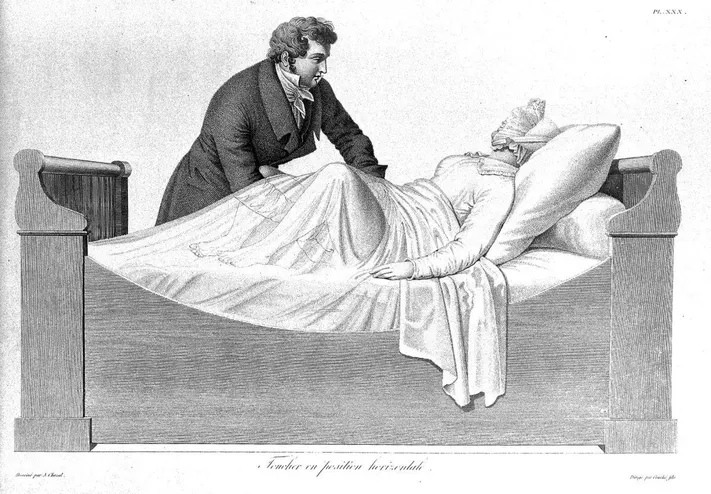

What stops a doctor from getting aroused while performing an intimate examination on a patient? She argues that after all they are ‘Also Human’. She extensively discusses different national and international guidelines (especially those of New Zealand and the UK) on the ethics of doctors’ relationships with their patients. These are real emotional and ethical challenges doctors face.

It was a very interesting book and I highly recommend it, to doctors and non doctors alike.